By Charlotte C.S. Rulkens, Hans van Eyghen, Rachel S. A. Pear, Rik Peels, Lex M. Bouter, Maartje Stols-Witlox, Gijsbert van den Brink, Sabrina Meloni, Edwin Buijsen, René van Woudenberg

In the past few years, a variety of articles have examined why attempts to replicate studies in biomedical, natural and social sciences often are without success. These debates on the so-called ‘replication crisis’ led Rik Peels and Lex Bouter in 2018 to ask the question: What about replication in the humanities? Scholars in the humanities go about their research in other ways than those in the sciences, because of the difference in the sources, data and methods they work with, the type of questions they try to answer and the purposes they aim to serve. But two of the things that both domains have in common, is that they aspire to acquire knowledge that is not largely dependent on the idiosyncrasies of the researcher and that their future studies often relate to or build upon the findings of previous ones. Might replication studies be a useful way to corroborate findings in the humanities? If so, what would they look like in various fields within the humanities and how would they differ from replication in the biomedical, natural and social sciences? What aims would they strive for in terms of epistemic progress? What can the humanities learn from replication studies in the sciences and vice versa? In addition to this, we need to ask whether and how, as Peels and Bouter introduced, replication might contribute to the trustworthiness of research in the humanities. Furthermore, concerns regarding replication studies in the humanities voiced by other scholars, like Leonelli and Penders, Holbrook and De Rijcke, call for further investigation.

At the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, we have set out to explore the strengths and limitations of replication studies in the humanities in practice. We are doing so by replicating two original studies: one in the field of art history, the other in the field of history of science and religion. In this blog, we outline the design, purposes, and aims of these projects and explore some of the challenges.

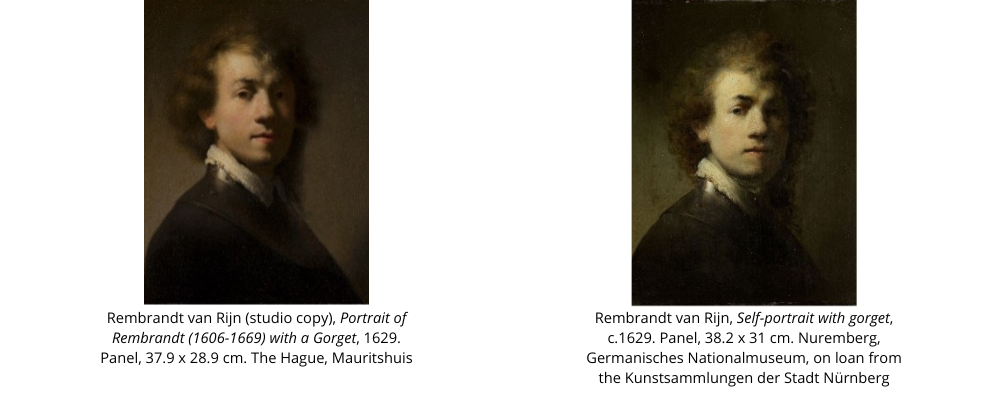

The art history case: Attributing two portraits of Rembrandt

The art historical study concerns the attribution of two portraits of Rembrandt that are in the collections of, respectively, the Mauritshuis in The Hague and the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg. Before publication of the original study by Edwin Buijsen and Jørgen Wadum in 1999 and 2000, the version in The Hague was generally accepted as painted by Rembrandt himself. The one in Nuremberg was considered a copy based on the The Hague painting, made by one of the students in Rembrandt’s studio. These attributions were reversed after the unexpected discovery of an underdrawing in the The Hague version, for Rembrandt was not known to have used underdrawings. The replication study will address the questions raised in the original study: How do these two versions relate to each other? Who made the version in The Hague and who painted the one in Nuremberg?

The art historical replication study required some preliminary steps before we could set up the study design. Since the research was published multiple times and in different forms, we first identified the most important publications. Second, as no formal study protocol had been formulated, we needed to make a detailed reconstruction of the original study, based on the original publications, archival sources and interviews with the original authors. Based on this reconstruction we decided to carry out both a reproduction and a conceptual replication. This is because comparing a reproduction - when successful - with a conceptual replication may provide more insights into the outcomes and potential of a conceptual replication. Furthermore, the examination techniques used in the original study have improved over the years. The use of new and modernized study methods in a conceptual replication enables a triangulation of the findings of the original study (i.e., trying to answer the same question by using different kinds of data).

The history case: The relation between religious and scientific reform

Chapter three of John Hedley Brooke’s seminal 1991 book Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives, studies the relation between the Protestant reformations and receptivity to scientific developments in the 16th and 17th centuries. Brooke investigates responses to the Copernican heliocentric theory as a test-case to analyze the responsiveness to new scientific ideas among Protestants and Catholics from c.1550 to c.1700. He concludes that Protestants were not necessarily more inclined to accept heliocentrism than Catholics (as scholars had previously argued) and that willingness to take on new ideas was due to the mixing of social and theological factors.

We will carry out both a direct and a conceptual replication of Brooke’s original study. The direct replication consists of a re-testing of Brooke’s original findings concerning the relation between religious and scientific reform. This is done by carrying out a literature review of the secondary sources referenced by Brooke himself, i.e. Protestant and Catholic responses to Copernicanism, and of new sources unavailable to or not used by Brooke. For the conceptual replication, the research protocol has been changed to review historians’ analyses of Jewish responses to Copernican thought. The aim is to investigate whether Jewish responses to Copernican thought corroborate Brooke’s findings, using the Jewish case as parallel to the Catholic one. The study design opens up a way for triangulation and contributes to the diversification of this particular field of research. Furthermore, exchanges with researchers at Utrecht University working on the project Once more, with feeling. Replications in history offer a valuable opportunity for comparing the possibilities and limitations of our different approaches.

Challenges in executing a replication study in the humanities

One of the challenging aspects of the projects is that we need to operate on two levels: on the first level, we conduct the actual replications by tackling the original research questions once more. The second level consists of exploring the strengths and limitations of replication studies in the humanities. This means that the team simultaneously needs to take the meta-perspective and to reflect jointly on the design and execution of our replication studies. This not only poses practical challenges, but is also cause for reflection on the fundamentally different perspective we adopt. Furthermore, in the art history project, it quickly became clear that connoisseurship and interpretation are interesting and sometimes problematic aspects when it comes to replication. The epistemic value in exploring replication studies in art history might therefore go beyond the goal of corroboration of findings, they may lead to further insights into connoisseurship in general.

Diaries and documentation along the way

Because of the exploratory nature and meta-level of the projects, our documentation of the process is crucial. Finding ways to do so properly and efficiently is one of the challenges we face. We document in the first place by updating our preregistrations with amendments if needed. But also by making video recordings and meeting minutes, saving field notes, agendas, discussion documents and email exchange. These sources not only serve the replicability of our own studies, but they will also inform our analysis of the strengths and limitations of replication in the humanities. Finally, a meta-level analysis of the projects is being carried out by the researchers of Replication in Action, which seeks to gain a better understanding of how replications are executed in practice.

New grounds

With these replication projects in the humanities, we are venturing into new territory. And from new grounds, new questions arise and new pitfalls are revealed. In the early stages of the art history project, for example, it already became clear that, as in the sciences, thorough documentation and reporting are crucial for creating the very possibility of carrying out a replication study. A project on replication immediately reveals knowledge gaps that are the result of incomplete documentation of methods and approaches, argumentation, data and interpretation. The first phase of the projects furthermore demonstrated that replication is a tailor-made job that has to be designed for the specific aims and the type of research one is re-doing. This will make the formulation of general recommendations challenging. Our two studies induce questions that were earlier overlooked related to the preconditions for, distinctions between, boundaries and possible purposes of replication studies. We are curious what other points of attention, strengths and limitations we will discover. We promise that towards the end, we will follow-up with another blog to share results of the projects.

Further reading

Do you want to know more about the studies described above? The preregistration of the Rembrandt replication and the preregistrations of the direct replication and conceptual replication of the science and religion study are published on the OSF registries website.

Embedding

These studies are part of the larger research Epistemic Progress in the University, carried out at the Abraham Kuyper Center, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam. The main question the larger project addresses is: How can universities enable epistemic progress—both policy-wise and in the humanities? The Rembrandt replication study is carried out in close collaboration with the Mauritshuis, The Hague. The Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg is an important facilitator of the technical research being carried out.

Funding

Epistemic Progress in the University is funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, grant number TWCF0163. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Templeton World Charity Foundation. The funder has no role in study design, data collection, analysis or publication of the research.

About the authors

Charlotte C.S. Rulkens works as a Research Associate on the Rembrandt replication at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She is an art historian specialized in Dutch 17th century painting. Prior to her appointment at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Charlotte worked as a curator at the Mauritshuis in the Hague, where she contributed to various exhibitions and catalogues.

Charlotte C.S. Rulkens works as a Research Associate on the Rembrandt replication at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She is an art historian specialized in Dutch 17th century painting. Prior to her appointment at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Charlotte worked as a curator at the Mauritshuis in the Hague, where she contributed to various exhibitions and catalogues.

Hans van Eyghen works as Postdoc on the science and religion replication at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Tilburg University. He holds an MA in theology and an MA in philosophy from the Catholic University of Leuven and a PhD in philosophy from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Hans van Eyghen works as Postdoc on the science and religion replication at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Tilburg University. He holds an MA in theology and an MA in philosophy from the Catholic University of Leuven and a PhD in philosophy from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Rachel S. A. Pear works as a Postdoc on the science and religion replication at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She also is a Research Fellow at the University of Haifa and the coordinator of the MENA Science and Religion researchers’ network. Rachel received her PhD from Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, within the Graduate Program on Science Technology and Society.

Rachel S. A. Pear works as a Postdoc on the science and religion replication at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She also is a Research Fellow at the University of Haifa and the coordinator of the MENA Science and Religion researchers’ network. Rachel received her PhD from Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, within the Graduate Program on Science Technology and Society.

Rik Peels is Associate Professor in Philosophy and Religion & Theology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, co-leads the project Epistemic Progress in the University, and leads the ERC-funded project Extreme Beliefs.

Rik Peels is Associate Professor in Philosophy and Religion & Theology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, co-leads the project Epistemic Progress in the University, and leads the ERC-funded project Extreme Beliefs.

Lex M. Bouter is Professor of Methodology and Integrity at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and at the Amsterdam University Medical Centers. In the past he was Professor of Epidemiology and he served his university as its rector for seven years. His current research interests are research integrity and responsible conduct of research. More details can be found on his profile page.

Lex M. Bouter is Professor of Methodology and Integrity at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and at the Amsterdam University Medical Centers. In the past he was Professor of Epidemiology and he served his university as its rector for seven years. His current research interests are research integrity and responsible conduct of research. More details can be found on his profile page.

Maartje Stols-Witlox is an art historian and paintings conservator. She is currently Associate Professor at and Programme Director of the Master’s programme in Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage at the University of Amsterdam. In her research into historical painter’s practices, reconstruction or replication takes a central role.

Maartje Stols-Witlox is an art historian and paintings conservator. She is currently Associate Professor at and Programme Director of the Master’s programme in Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage at the University of Amsterdam. In her research into historical painter’s practices, reconstruction or replication takes a central role.

_crop.jpg?width=100&height=100&name=Gijsbert%20van%20den%20Brink%202%20(if%20other%20one%20is%20too%20low%20res)_crop.jpg) Gijsbert van den Brink is Professor of Theology & Science at the Faculty of Religion and Theology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and previously served as a Professor in the History of Reformed Protestantism. His current research focuses on interactions between science and religion.

Gijsbert van den Brink is Professor of Theology & Science at the Faculty of Religion and Theology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and previously served as a Professor in the History of Reformed Protestantism. His current research focuses on interactions between science and religion.

Sabrina Meloni is Paintings Conservator at the Mauritshuis in The Hague. She obtained her MA in Art History from the Leiden University, followed by a 5-years post-graduate program in Conservation of Paintings and Painted Objects at SRAL (Limburg Conservation Institute) in Maastricht. The focus of her work is on the conservation and technical research of 17th-century Dutch paintings.

Sabrina Meloni is Paintings Conservator at the Mauritshuis in The Hague. She obtained her MA in Art History from the Leiden University, followed by a 5-years post-graduate program in Conservation of Paintings and Painted Objects at SRAL (Limburg Conservation Institute) in Maastricht. The focus of her work is on the conservation and technical research of 17th-century Dutch paintings.

Edwin Buijsen is Head of Collection and Research at the Mauritshuis in The Hague. He received his PhD in Art History at the Radboud University in Nijmegen. Edwin contributed to various exhibitions at the Mauritshuis and published widely on Dutch 17th century painting. He was involved in the original Rembrandt study that is aimed to be replicated as part of this project.

Edwin Buijsen is Head of Collection and Research at the Mauritshuis in The Hague. He received his PhD in Art History at the Radboud University in Nijmegen. Edwin contributed to various exhibitions at the Mauritshuis and published widely on Dutch 17th century painting. He was involved in the original Rembrandt study that is aimed to be replicated as part of this project.

René van Woudenberg is Professor of Philosophy at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam where he teaches Epistemology and Metaphysics. He is also director of the Abraham Kuyper Center at the Philosophy Department at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

René van Woudenberg is Professor of Philosophy at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam where he teaches Epistemology and Metaphysics. He is also director of the Abraham Kuyper Center at the Philosophy Department at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

References

Brooke, John Hedley, Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

Buijsen, Edwin, ‘Self portrait with gorget’ and ‘Portrait of Rembrandt with a gorget’, in Rembrandt by Himself, ed. by Christopher White and Quentin Buvelot (The Hague: Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis/ London: National Gallery Publications Limited/ Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 1999), pp. 112-117.

Eyghen, H. van, Pear, R.S.A., Peels, R., Bouter, L., Brink, G. van den, Woudenberg, R. van, ‘Testing the relation between religious and scientific reform. A direct replication of John Hedley Brooke’s 1991 study’, Preregistration Open Science Foundation (2022), DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/XNDWT.

Leonelli, S., ‘Rethinking Reproducibility as a Criterion for Research Quality’, (preprint) 2018, DOI: 10.1108/S0743-41542018000036B009.

Pear, R.S.A., Eyghen, H. van, Peels, R., Bouter, L., Brink, G. van den, Woudenberg, R. van, ‘A conceptual replication of Brooke’s 1991 chapter: Do Jewish responses to Copernican thought corroborate the findings?’, Preregistration Open Science Foundation (2023), https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/J8N59.

Peels, R., Bouter, L., ‘The Possibility and Desirability for Replication in the Humanities’, Palgrave Communications 4.95 (2018), DOI: 10.1057/s41599-018-0149-x, reprinted in Quantitative Methodologies: Novel Applications in the Humanities and Social Sciences.

Peels. R., Bouter, L. ‘Replication and Trustworthiness’, Accountability in Research: Policies and Quality Assurance, DOI: 10.1080/08989621.2021.1963708

Penders, B., Holbrook, J.B., de Rijcke, S., ‘Rinse and Repeat: Understanding the Value of Replication across Different Ways of Knowing.’ Publications, 7, 52 (2019) DOI: 10.3390/publications7030052.

Rulkens, C. C. S., Peels, R., Bouter, L., Stols-Witlox, M., Meloni, S., Buijsen, E. ‘The attribution of two portraits of Rembrandt revisited: A case study of replication in art history’, Preregistration Open Science Foundation (2022), DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/5CWG7

Wadum, Jørgen, ‘Rembrandt under the Skin. The Mauritshuis "Portrait of Rembrandt with Gorget" in retrospect’, Oud Holland. Journal for Art of the Low Countries, 114, 2 (2000), 164-187.

6218 Georgia Avenue NW, Suite #1, Unit 3189

Washington, DC 20011

Email: contact@cos.io

Unless otherwise noted, this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

Responsible stewards of your support

COS has earned top recognition from Charity Navigator and Candid (formerly GuideStar) for our financial transparency and accountability to our mission. COS and the OSF were also awarded SOC2 accreditation in 2023 after an independent assessment of our security and procedures by the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA).

We invite all of our sponsors, partners, and members of the community to learn more about how our organization operates, our impact, our financial performance, and our nonprofit status.