There is an active discussion in the open science community about what "preregistration" means in practice and what researchers should conclude about research that has been preregistered. These two intertwined challenges, one about knowledge production and one about knowledge consumption, are useful lenses through which to look at broader challenges in the growing open science community. Addressing these challenges will involve new roles for individuals as well as changes to our collective systems for sharing and evaluating knowledge, changes that are only possible through community support. Whether or not you have heard of preregistration before, these discussions are worthy of consideration.

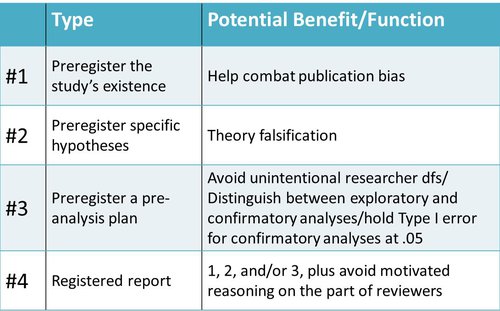

I run workshops for COS with researchers around the country to introduce open science practices like preregistration and I always start with a definition. I tell researchers that preregistration means putting your research plan in a public repository before you run the study and that the benefits of preregistration depend directly on how much information you put into it. In a recent blog post titled "Preregistration is a Hot Mess. And You Should Probably Do It.” Professor Alison Ledgerwood from UC Davis uses this wonderful chart to lay out the main potential benefits from preregistration and what information is needed to achieve each one:

Shortly thereafter a presentation (p.24) by Stanford's John Ioannidis outlined five different "levels" of preregistration and the information required for each.

Both ideas underscore the variability in content and goals that may be present in any individual preregistration. This variability presents two challenges for researchers: 1) How to make sure they include the right information in their own preregistrations to achieve the benefits they wish and 2) What, if anything, the existence of a preregistration tells them about other people's research. For me the line between these two challenges shows the limitation of what we can achieve with education efforts alone.

We can, and do, work to directly help interested researchers learn how to preregister their own work to get whichever benefits of preregistration that they wish (email prereg@cos.io if you want some specific advice!). Yet, even if every researcher were looking for the same benefits from preregistration, the mere existence of a preregistration only tells you about that researcher's intentions. Knowing these intentions may be useful in evaluating the research that followed but the biggest benefit of preregistration comes not from this signal of researcher intent but from the actual content of the preregistration and the additional transparency it brings to the research process. Evaluating this kind of content is beyond what education, or even the efforts of individual researchers, can accomplish alone and requires community action.

Transparent practices like preregistration and sharing data, materials, and analysis code from research enable others in the field to understand a particular study by increasing the information about that study available for review. This increase in information can also act to reduce the number of studies that any one researchers can practically review during the time they have available. Part of the discussion about signals of transparency and the definition of preregistration is a response to this increase in the amount of information produced; we are looking for signals about research quality and researcher practice to help them navigate this growing volume of information. This is a good problem to have because it means that "open science" is becoming just "science" but sorting through this kind of information boom can be a real problem and one that will only increase as these open science practices continue to become more normal.

Building community tools to address this need is one of the great areas of growth and innovation in the open science community right now. Those tools take many forms, from departments outlining open science goals for their research, journals that verify the computational reproducibility of published articles (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), community-moderated preprint services, or journals that published Registered Report, in which the alignment between the preregistration and the final results are verified. Each of these efforts help produce useful signals for the community about how research is conducted and what information is available about that research. How to organize these systems and what kind of information they should present to the community is still evolving, see for instance the recent preprint by Tom Hardwicke and John Ioannidis exploring the Registered Reports landscape and ways in which it may not line up with expectations about preregistrations more generally. The continued growth and evolution of these tools is vital to the growth of open science.

It can be easy, especially if you are new to the field, to get lost in the discussions of individual open science practices like preregistration and conclude that open science is just about changing what researchers publish to the world. While that work is important, what this individualistic focus misses is the vital work that we all do together to help spread open science practices and to better process all the new information that open science practices produce. There are a host of ways you can make a difference in open science, whether that means modifying your own research practices, advocating for policies at the department level, or participating in community comment and review processes at the preprint or journal level, there is always room for growth and improvement.

6218 Georgia Avenue NW, Suite #1, Unit 3189

Washington, DC 20011

Email: contact@cos.io

Unless otherwise noted, this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

Responsible stewards of your support

COS has earned top recognition from Charity Navigator and Candid (formerly GuideStar) for our financial transparency and accountability to our mission. COS and the OSF were also awarded SOC2 accreditation in 2023 after an independent assessment of our security and procedures by the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA).

We invite all of our sponsors, partners, and members of the community to learn more about how our organization operates, our impact, our financial performance, and our nonprofit status.